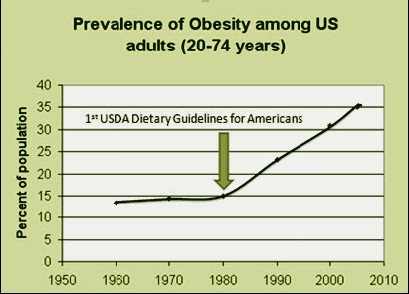

I’m shocked that the USDA’s Food Pyramid, and its principles still exists. Since its inception, obesity rates have skyrocketed from 15% to 35% of the population. The low fat, high carb diet does NOT work for most people. How often do you hear people today touting how much weight they’ve lost from cutting back on carbs, or how good they feel from their “ketogenic” diets? I hear it all the time. On the flip side, when’s the last time you’ve heard someone say that they lost weight from switching to cereal and cutting out egg yolks? This article from the Weston A. Price Foundation reveals some of the details and motives behind the USDA’s recommendations and what they try to tell us a “healthy food is. It’s mind blowing and mind numbing at the same time.

The USDA’s Pyramid Scheme

We Need a New Way to Define “Healthy”

Presentation at the Weston A. Price Foundation press conference on the USDA Dietary Guidelines, February 14, 2011.

I am a PhD candidate in Nutrition Epidemiology at the University of North Carolina. I represent the Healthy Nation Coalition, a public health advocacy group dedicated to changing our definition of healthy food. But I also represent all those Americans who have tried to eat a healthy diet according to the USDA’s definition and have become overweight, obese, and sick in the process. I was one of those people—obese and sick—when I ate according to the guidelines.

I went back to school because I worked at a Duke Clinic, where I met a lot of people just like me, people who were struggling with weight gain and poor health, trying to force their bodies to be well on a dietary pattern never proven to have specific health benefits. That’s right, the recommended diet has not even been tested.

We know that it has not been tested because the USDA makes this statement in the 2010 Dietary Guidelines document: “The [USDA] food patterns were developed to meet nutrient needs . . . while not exceeding calorie requirements. Though they have not been specifically tested for health benefits they are similar to the DASH research diet and consistent with most of the measures of adherence to Mediterranean-type eating patterns (emphasis added).”

The first USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans were released in 1980. After sixteen years of following the recommended lowfat, grain-and-cereal based diet, I was sixty pounds overweight, fighting to get my body back. I ate less; I exercised more. I finally lost fifteen pounds. I was also hungry and tired and miserable— and what’s worse, I couldn’t lose any more weight without starving myself.

After a lot of research, I found—and the patients at the clinic found—that when we ate foods that the USDA had been telling us not to eat— foods like eggs, broccoli with butter, greens with fatback, and even the occasional steak—we felt better, lost weight, and got healthier.

For the patients I met with type-2 diabetes, they could get their blood sugars under control and reverse their symptoms, instead of having the disease progress to loss of kidney function, eyesight, or even a limb. When they changed their diets to include fat and reduced the highly processed grains and cereals that the Food Pyramid is built on, they were able to reduce or stop taking medication. They got better; they lost weight. It happened time and time again. And they wondered, as I did, why we’ve been told that the only way to be healthy is to follow the USDA guidelines, a diet that doesn’t work for me, for them, nor for many Americans.

From the start, our dietary recommendations have been based as much on politics as on science. The first set of dietary goals was written by political staffers, not scientists or nutritionists.1 They were based on the as-yet-unproven theory that reducing dietary fat would reduce heart disease, diabetes, and obesity.2 They directed Americans to consume less fat and more carbohydrate.

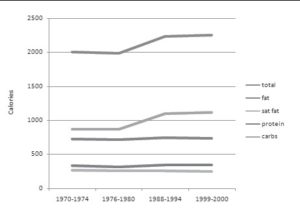

These guidelines have remained remarkably consistent for the past thirty years and Americans have done their best to follow them. We have lowered our fat intake, and we have increased our carbohydrates (Figure 1). Since the first guidelines, the number of obese Americans has more than doubled (Figure 2); the number with type-2 diabetes has tripled.

The dramatic rise in obesity in America began in the early 1980s after the release of the first Dietary Guidelines for Americans, after which Americans gradually reduced the fat in their diets and consumed more carbohydrate foods.

| FIGURE 1: Energy intake changes during the obesity epidemic.3 | FIGURE 2: Dramatic Rise in Obesity among U.S. Adults (20-74 Years) Since Implementation of the USDA Dietary Guidelines.4 |

|

|

How did this happen? The USDA blames our “obesogenic” environment.5 But the USDA creates the policies that control nearly every aspect of our food environment. Its primary mandate is to increase consumer demand for U.S. agricultural products. The primary promotional tool for U.S. food products is the Dietary Guidelines in which USDA defines “healthy food.” This definition of “healthy” shapes what consumers demand and what food industries provide.

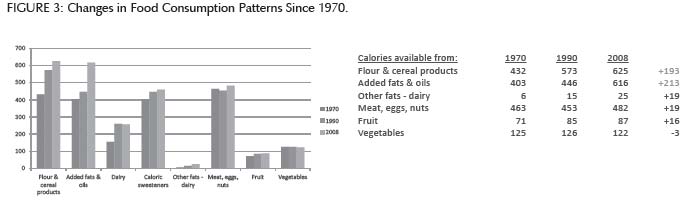

Thanks to these policies, cheap grain and cereal-based foods are everywhere and are marketed as an important part of a healthy diet. During the past thirty years, the energy available from processed flour and cereal products and the added fats and oils in them has increased by nearly two hundred calories, while the energy available from less processed foods—meat, eggs, nuts, fruits, and vegetables— has increased by less than twenty calories (Figure 3).5

Thanks to these policies, cheap grain and cereal-based foods are everywhere and are marketed as an important part of a healthy diet. During the past thirty years, the energy available from processed flour and cereal products and the added fats and oils in them has increased by nearly two hundred calories, while the energy available from less processed foods—meat, eggs, nuts, fruits, and vegetables— has increased by less than twenty calories (Figure 3).5

Since the calorie increase in our diet over the past thirty years has come almost entirely from grain-based foods, many nutrition experts now agree that it’s not just how much we are eating, but what. They believe our lowfat diet recommendations have helped fuel our nation’s health crisis.6 Yet the USDA has disregarded the current scientific evidence and expert opinion, insisting that “a healthy diet is high in carbohydrates.”5 Why isn’t it?

Since the calorie increase in our diet over the past thirty years has come almost entirely from grain-based foods, many nutrition experts now agree that it’s not just how much we are eating, but what. They believe our lowfat diet recommendations have helped fuel our nation’s health crisis.6 Yet the USDA has disregarded the current scientific evidence and expert opinion, insisting that “a healthy diet is high in carbohydrates.”5 Why isn’t it?

Humans have an inherent preference for sugary and starchy foods. The mechanism that makes these foods addictive has recently been clarified.7 We are not addicted to fat and salt, which on their own have limited appeal. Could you eat a stick of butter by itself? Instead, we are addicted to the sugary, starchy foods that happen to come with fat and salt. Add some bread. Now how much butter can you eat?

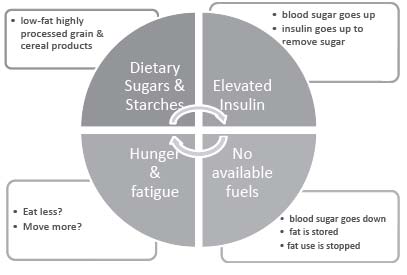

Dietary sugars and starches cause our insulin to rise, which encourages fat storage and prevents fat burning. Then we have no fuel: we’re hungry, we’re tired and we’re addicted. Chronically elevated insulin is also an independent risk factor for diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease.8

Scientists know this. But when scientific evidence contradicts the USDA’s definition of healthy, the USDA ignores the science—why shouldn’t they? There is no one policing the policymakers. There are no consequences to the USDA if their guidelines don’t work.

But there are plenty of consequences to us. This cannot be stated strongly enough: the Dietary Guidelines, because they are not based on objective scientific evidence, have caused, and will continue to cause, harm.

The 2010 Guidelines focus on counting and controlling calories, when science shows us that restrictive eating patterns in children and teenagers actually lead to an increased risk of obesity and other eating disorders.9,10 Many men and women all over America go hungry trying to compel their bodies to respond to a lowfat diet with increasingly lowered calories. Few of them will succeed. As a nation, we pay the price in rising health care costs, diminished quality of life, and the loss of loved ones. In the meantime, the USDA continues to tighten its grip on food and nutrition policy in America.

If we want to fix the obesity crisis, the USDA tells us, it’s up to us: just eat less and move more. But that’s not what the USDA really wants.

Due to their own policies, food prices and production at the farm level are both flat.11 The only way to “grow” the agricultural sector is to increase processing. This is where the money is. Look closely at the “eat less” recommendations in the guidelines; they are a veiled promotion of foods the USDA want us to eat more of.

“Fear-the-fat” messages that are not based in science steer us away from minimally processed foods like eggs and meat. Instead, we are encouraged to buy enormously profitable, fortified and enriched products that are virtually devoid of nutrition until they are transformed by the miracles of modern chemistry to meet the USDA’s definition of “healthy.”

The Weston A. Price Foundation has helped educate the public on the importance of fats in the diet. The other two major calorie sources are protein and carbohydrate. Protein is crucial to good health.5 Carbohydrates are biologically unnecessary.12

That’s the nutrition part; here’s what’s happening with actual food, as shown by the two breakfasts below.

The first breakfast contains eggs, sausage and cheese. The USDA says we should eat less of these foods. But this breakfast contains just the right amount of protein, no sugar, ten total ingredients (all of them pronounceable), and the whole meal costs less than a dollar. From a meal like this, a larger percentage of that dollar is getting back to the farmer, because less of it is going for packaging and processing.

The second breakfast is composed of the foods that the USDA says we should eat more of. It contains very little protein, over forty grams of sugar, and over forty ingredients. And it costs over two dollars, of which the farmer will see a very small percentage; most of it will go to the food manufacturers who package and process cheap grain and cereal products.

The USDA doesn’t really want us to “eat less and move more.” They want us to “eat less and buy more.” The USDA-approved breakfast is “plant based” as the guidelines recommend, but filled with unpronounceable ingredients. Plant-based, lowfat “frankenfood” products are anything but natural.

| SIDEBAR HEALTHY BREAKFAST: NOT USDA APPROVED | ||||||

| A TALE OF TWO BREAKFASTSA breakfast of two eggs, sausage and cheese has the same amount of calories as the USDA approved breakfast of oatmeal, fruit juice and soy yogurt, but contains no sugar and almost four times as much protein and costs half as much. Such a breakfast is demonized by government officials as containing too much cholesterol and saturated fat. | Calories | Protein (grams) |

Sugar (grams) |

Price/ Serving |

Number of Ingredients |

|

| Sausage (one 1.5 oz patty) |

170 | 12 | 0 | 0.50 | 5 | |

| Eggs (2) | 140 | 12 | 0 | 0.22 | 1 | |

| Cheese (1/4 cup) | 100 | 6 | 0 | 0.21 | 4 | |

| Total | 410 | 30 | 0 | $0.93 | 10 | |

| UNHEALTHY BREAKFAST: USDA APPROVED | ||||||

| Instant oatmeal (1 package) |

160 | 4 | 7 | 0.37 | 17 | |

| Veg/Fruit Juice (1 8oz can) |

100 | 0 | 23 | 0.93 | 11+ | |

| Soy yogurt (6 oz) |

150 | 4 | 21 | 0.74 | 15 | |

| Total | 410 | 8 | 44 | $2.04 | 43+ | |

The massive monoculture crops from which these fake foods are made deplete our topsoil and poison our rivers with pesticide and fertilizer run-off. A tofu “hot dog” is not good for you, it’s not good for the farmer, and it’s not good for the environment. We know that the vegan movement, Oprah’s Vegan Week, and Michal Pollan’s “eat mostly plants” message are well-intended, but eating fewer animal products means eating more Monsanto products.

|

SIDEBARIN THE FACE OF CONTRADICTORY EVIDENCE REPORT OF THE 2010 DIETARY GUIDELINES ADVISORY COMMITTEEAn article by Adele Hite and others, published in the journal Nutrition (26(2010) 915-924), takes the 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) to task for ignoring or misrepresenting evidence that exonerates saturated fats and shows high-carbohydrate diets may be to blame for the increasing rates of obesity and chronic disease in the U.S.. “Although appealing to an evidence-based methodology, the DGAC Report demonstrates several critical weaknesses, including use of an incomplete body of relevant science; inaccurately representing, interpreting or summarizing the literature; and drawing conclusions and/or making recommendations that do not reflect the limitations or controversies in the science.An objective assessment of evidence in the DGAC Report does not suggest a conclusive proscription against low-carbohydrate diets.”The report of Hite and others notes that over the last thirty years, as obesity rates have doubled, average daily calories from fatty foods like meats, eggs and nuts has increased only 20 calories per day, while average daily calories from flour and cereal products has increased by nearly twenty times that amount. In other words, the American diet has shifted in the direction recommended since the 1977 dietary goals to reduce overall fat and saturated fat in the diet. Total and saturated fat intakes have decreased as a percentage of calories whereas carbohydrate intake has increased.The Committee created a Nutrition Evidence Library (NEL) in order to justify the latest Guidelines as “evidence based.” Yet the NEL contains evidence that is not consistent with DGAC conclusions. For example, several studies in the NEL demonstrate equivalent or increased weight loss on low-carbohydrate diets with similar caloric intake; and several studies in the NEL demonstrate equivalent or increased weight loss on low-carbohydrate diets that do not explicitly control calories or impose restrictive eating behaviors. In fact, 47 percent of the studies cited in the NEL demonstrate that low-carbohydrate or high-protein diets are more effective for weight loss.Regarding the effects of saturated fats on cholesterol levels and rates of cardiovascular disease and type-two diabetes, the Committee stated that “strong evidence” indicates a positive association of saturated fats with these conditions. But the committee only included studies in the NEL that measured the effects of saturated fats in the presence of high levels of carbohydrates. Studies that looked at saturated fat consumption in low-carbohydrate diets were excluded. Most serious is the Committee’s exclusion of a recent large meta-analysis, which found no substantial evidence linking saturated fat with an increased risk of heart disease.The DGAC Report suggests that the replacement of saturated fats with monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fats invariably creates positive risk factor outcomes. Yet studies cited by the DGAC Report demonstrated increases in atherogenic lipoprotein levels, decreases in HDL-cholesterol and varied metabolic responses to lowered saturated fat in several population groups. The Committee cited a meta-analysis by Jakobsen and others as evidence of “a significant inverse association” with coronary events when substituting polyunsaturated oils for saturated fats. But the DGAC misrepresented the actual findings of the meta-analysis. The association was weak overall and significant only for women younger than sixty. For all men in the study and for women over the age of sixty, there was no significant association. The DGAC Report also claims that lowfat diets are beneficial for diabetes; again, the studies cited only show the results of diets high in both carbohydrates and fats. No studies that looked at decreased carbohydrate intake for achieving blood sugar control were considered by the Committee. One reason the Committee claims that decreasing carbohydrate intake is not advisable is that it would necessarily restrict fiber intake, although support for the benefits of fiber intake is limited and non-conclusive. The DGAC Report also advises Americans to shift to more “plant-based” diets and “consume only moderate amounts of lean meats, poultry and eggs.” Yet the Committee itself notes that evidence linking meat consumption with chronic disease is “moderate, limited, insufficient and inconsistent,” and acknowledges that plant protein confers no specific health benefits and may in fact present nutritional inadequacies. One of the greatest limitations of the DGAC Report is the recommendation to reduce salt consumption. Yet a Cochrane review concluded that “intensive interventions [involving salt reduction] unsuited to primary care or population prevention programs provide only minimal reductions in blood pressure during long-term trials.” The report of Hite and others concludes “. . . scientific evidence in favor of [DGAC] recommendations remains inconclusive, and we must consider the possibility that the ‘potential for harmful effects’ has in fact been realized.” The prevalence of overweight and obesity in the U.S. has increased dramatically in the past three decades and the number of Americans diagnosed with type-two diabetes has tripled. Yet the DGAC insists that their recommendations for more of the same are completely supported by the science. To read the full report, go to http://www.spfldcol.edu/homepage/dept.nsf/91C8B01CAAC804C0852577C9006A5012/$File/Hite_Nutrition_2010.pdf. |

That said, we do not stand in opposition to either the food industry or to the humane treatment of animals. Both are crucial to the safe and adequate food supply that Americans deserve. But Americans also deserve to know the truth about nutrition. Our farmers deserve better support; our land deserves better care.

When the first Dietary Guidelines were created, our understanding of the relationship between nutrition, chronic disease, and the food environment was immature. We didn’t know what would happen when we chose to commit ourselves to a single dietary approach directed by a single government agency. The agency then could not have predicted the explosion of food products with lower fat content and higher sugar, starches, and profit margins.

The agency could not have predicted the advances in science that would uncover not only the addiction-like process that compels us to gobble up these foods, nor could they have predicted the mechanisms that reveal how these foods can change the expression of our genetic material and predispose a generation of children to metabolic disorders, including obesity and diabetes.13,14 The agency could not have guessed that its recommendations would have especially devastating effects on minorities whom scientists believe may be genetically susceptible to diseases related to a diet high in processed grains and cereal products.15,16

But now we know better. The influence of the Dietary Guidelines has now greatly surpassed the assumptions surrounding the original mandates that made the USDA the lead agency in the area of nutrition. The U.S. Dietary Guidelines have become a powerful policy tool with far-reaching consequences that not only affect the daily food choices of Americans and the personal health outcomes that result, but the health of our environment, our economy, and our future.

No government agency should be given such power with so few checks and balances. The USDA tells us that the Guidelines were created with complete transparency. But transparency doesn’t help if the dice are loaded before the game begins.

As the Dietary Guidelines have grown in importance, they have outgrown their tenure at the USDA. What is needed now is an independent, authoritative body—perhaps an Office of Food and Nutrition Policy— that can coordinate the creation of our Dietary Guidelines with a full understanding and awareness of the complexity of human nutrition and its relationship to the environment, the economy, national security, and our future as a nation.

It’s time to call this 30-year-long experiment on the people of America to a halt.

Echoing its most identifiable icon, the USDA’s control of food policy is a pyramid scheme. And like all pyramid schemes, there is no benefit for the consumers and the farmers at the bottom. Only those at the top, the giants of the food industry, stand to profit from this system. It’s time to knock this pyramid down and find a new home for the Dietary Guidelines.

The USDA is fond of characterizing Americans as having too much on their plates. This description applies more accurately to the USDA itself. We must ask the USDA to do what its 2010 Dietary Guidelines are insisting that all Americans do: to push away from the table and give up its control of the creation of the Guidelines.

| SIDEBARTHE NON-SCIENCE OF THE 2010 USDA DIETARY GUIDELINES COMMITTEE [E]vidence has begun to accumulate suggesting that a lower intake of carbohydrate may be better for cardiovascular health. Dr. Janet King, Chairwoman of the 2005 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee . . . [L]owfat. high-carbohydrate diets may modify the metabolic profile in ways that are considered to be unfavorable with respect to chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease and diabetes. Institute of Food and Medicine 2005 Macronutrient Report Healthy diets are high in carbohydrates. USDA 2010 Dietary Advisory Committee Report |

References :

1. Blackburn H. Interview with Mark Hegsted. “Washington— Dietary Guidelines.” Accessed January 24, 2011. http://www.foodpolitics.com/wp-content/uploads/Hegsted.pdf.

2. Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs of the United States Senate. Dietary Goals for the United States. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1977b.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in intake of energy and macronutrients—United States, 1971-2000. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004 Feb 6;53(4):80-2.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics, Division of National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Extreme Obesity Among Adults: United States, Trends 1976–1980 Through 2007–2008. Accessed February 1, 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/hestat/obesity_adult_07_08/obesity_adult_07_08.pdf.

5. United States Department of Agriculture. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010. Accessed July 15, 2010. http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/DGAs2010-DGACReport.htm.

6. Jameson, M. “A Reversal on Carbs.” Los Angeles Times. December 20, 2010. Accessed December 28, 2010. http://articles.latimes.com/2010/dec/20/health/la-hecarbs-20101220

7. Lustig, Robert. “Sugar, Hormones, and Addiction.” Presentation at the American Society for Bariatric Physicians, November 12, 2010.

8. Reaven, Gerald M. Insulin resistance: the link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Endocrinology Metabolism Clinics of North America. 2008 Sep; 37(3):581-601, vii-viii.

9. Haines J and Neumark-Sztainer D. Prevention of eating disorders and obesity: A consideration of shared risk factors. Health Education Research 2006, 21(6): 770-782.

10. Field 2003 Field A, Austin SB, Taylor CB, Malspeis S, Rosner B, Rockett H, Gillman M, Colditz G. 2003. Relation Between Dieting and Weight Change Among Preadolescents and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2003; 112: 900-906.

11. Pyle, George. Raising Less Corn, More Hell: The Case for the Independent Farm and Against Industrial Food. New York: Public Affairs, 2005.

12. Report of the Panel on Macronutrients, Subcommittees on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients and Interpretation and Uses of Dietary Reference Intakes, and the Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2005.

13. Smith J, Cianflone K, Biron S, Hould FS, Lebel S, Marceau S, et al. Effects of maternal surgical weight loss in mothers on intergenerational transmission of obesity. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009 Nov;94(11):4275-83.

14. Bland J. An Emerging 21st Century Perspective on Obesity: Beyond the Dogma of the Calorie. American Society of Bariatric Physicians Western Regional Obesity Conference, Regional Obesity Course. April 16, 2010.

15. Zamora D, Gordon-Larsen P, Jacobs DR Jr, Popkin BM. Diet quality and weight gain among black and white young adults: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study (1985-2005). American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010 Oct;92(4):784-93.

16. Hoffman RP. Metabolic Syndrome Racial Differences in Adolescents. Current Diabetes Review 2009 Nov;5(4):259-265.

This article appeared in Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts, the quarterly journal of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Spring 2011.