Limiting sugar intake is always a good general rule of thumb. However, fruit (which is supposed to be healthy) has naturally occurring sugar in it. They key words are “naturally occurring”. If you’re eating a whole food such as an apple or clementine, you’re not just eating fructose. The foods we find in nature are uniquely packaged with minerals, enzymes, fiber, etc. All of which are designed to help us digest, assimilate, and eliminate these foods. Should we OD on watermelon at the next barbecue then? No. Moderation is key. The bigger takeaway is that when we are trying to limit sugars in the name of weight loss or insulin resistance, we need to focus most of our attention on omitting added sugars, lab-made sugars, and refined sugars. Those are the nastiest of culprits when it comes to metabolic syndromes. So sit back, peel an orange, and enjoy this short article from peterattiamd.com, which details the differences between fruit sugars and added sugars.

Is natural sugar from fruit just as ‘bad’ as added sugar?

This video clip is taken from episode #194 – How Fructose Drives Metabolic Disease with Rick Johnson, M.D., originally released on February 7, 2022.

SHOW NOTES

Whole, fresh fruit

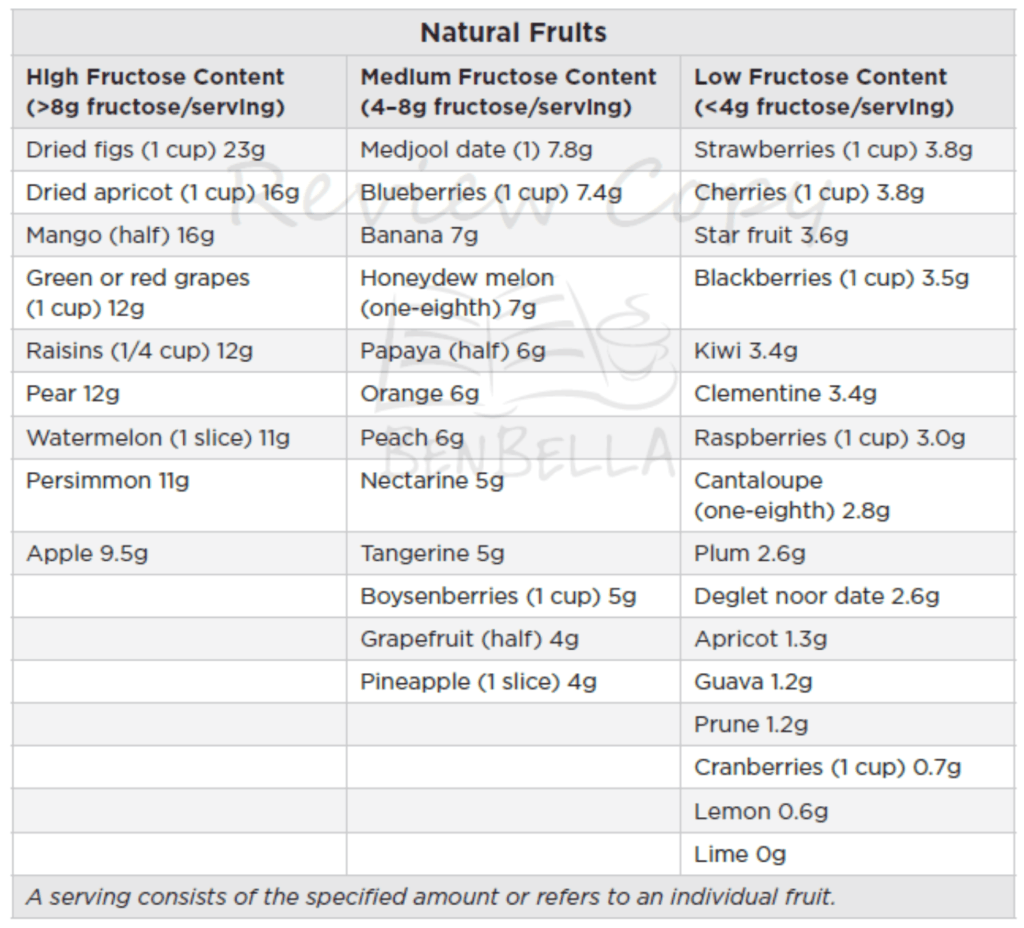

- Natural fruits are different; they have much less fructose in an individual fruit

- Fruit juice is made from multiple fruits

- Eat an orange and it has 6-8 grams of fructose, closer to 6 g of fructose and some glucose

- Rick thinks natural fruits are fine, even for someone with NAFLD (fatty liver)

- There are certain fruits that are high in sugar— mangoes, figs, dates

- Figs are very, very enriched in fructose; fFigs are probably something that we should avoid

- Apples and pears, plums, tend to be fairly high, around 9-10 grams

- Bananas are fairly high glycemic; they have a fair amount of fructose, but it’s probably in the range of 6-8 grams

- Most fruits are between 3-9 g, 10 g max, with the average being 4-6 g (see the table below)

- Some fruits have much less sugar— kiwi and berries (strawberries and blueberries)

- People should be encouraged to eat these

Figure 10. Fructose content per serving of fruit. Image credit: Nature Wants Us to Be Fat

- Rick did a study, they gave people a low sugar diet that was low in refined sugar and low in high fructose corn syrup

- Published in Metabolism in 2011, The effect of two energy-restricted diets, a low-fructose diet versus a moderate natural fructose diet, on weight loss and metabolic syndrome parameters: a randomized controlled trial

- One group got natural fruit, but was low sugar and low fructose

- It was sort of a modest total fructose intake

- The other group was restricted too

- It was a low fructose diet that was low fructose in all aspects

- They found equivalent improvement in metabolic syndrome in both groups

“The presence of natural fruit did not block the ability of the low sugar diet to improve metabolic syndrome” – Rick Johnson

- Peter notes, “The takeaway here is don’t drink it and don’t consume added sugar, and I think this is a difficult thing for people to differentiate. So added sugar is when a food has sucrose or high fructose corn syrup. These are typically the most common agents that are added to the food. So if you go and get a jar of pasta sauce, they have added sugar to it.”

- This is not the sugar naturally present in the tomatoes; it’s deliberately added to make it taste sweeter

- Rick agrees

- Remember the intestine acts as a shield for 4-6 grams of fructose

- Eating 4-5 g of fructose in a fruit is okay because the intestine’s going to provide protection

- In addition, there is fiber in a natural fruit and that slows the absorption so the concentration of fructose that goes to the liver is lower

- This results in less ATP depletion

Dried fruit

- Peter asks about dried fruits. How does apple chips compare to a whole apple, when considering equal amounts of calories?

“The trouble with dried fruit is that it still has all the fructose, but a lot of the good things are removed… Dried fruit is sort of like candy.” – Rick Johnson

RICK JOHNSON, M.D.

Richard Johnson is a professor of medicine in the Department of Nephrology at the University of Coloradosince 2008 and he’s spent the last 19 years being a division chief across three very prestigious medical schools. An unbelievably prolific author, Rick has well over 700 publications in JAMA, New England Journal of Medicine, Science, et Cetera. He’s lectured across 40 countries, authored two books, including The Fat Switch, and has been funded extensively by the National Institute of Health (NIH). His primary focus in research has been on the mechanisms causing kidney disease, but it was in doing this that he became really interested in the connection between fructose (and fructose metabolism) and obesity, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, and metabolic disease